Fifth Sunday of Lent (Year C)

St. Richard of Chichester, Bishop; Blessed Luciano Ezequiel and José Salvador Huerta-Gutiérrez, Laymen and martyrs

Is 43:16-21;

Ps 126;

Phil 3:8-14;

Jn 8:1-11

The Lord has done great things for us

BIBLICAL-MISSIONARY COMMENTARY

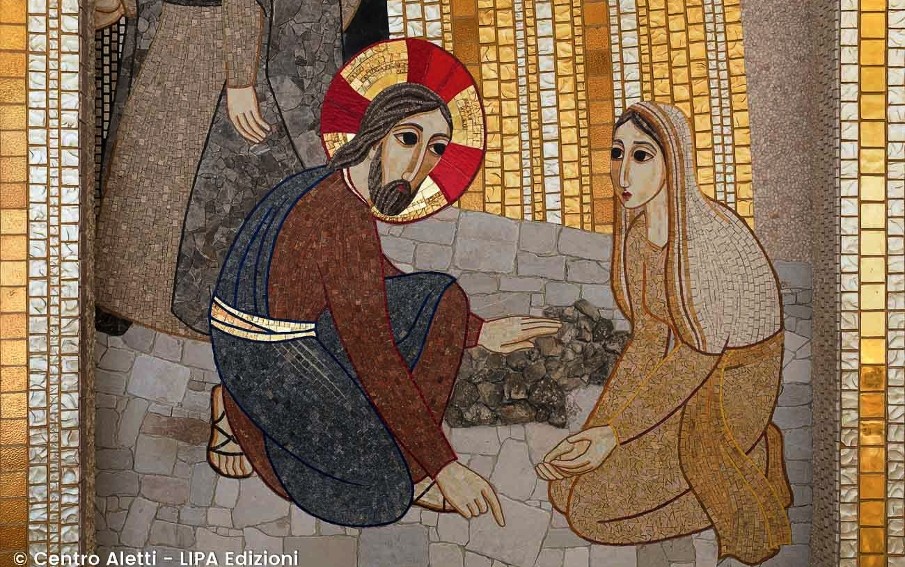

Misera et Misericordia “The Misery and Mercy”

With this fifth Sunday of Lent, we are approaching the final phase of the Lenten Journey. It is actually the last “ordinary” Sunday of Lent, because the next one will be Palm Sunday and the beginning of Holy Week, which culminates with the Easter Triduum. Therefore, we can already see on the horizon Easter, which celebrates Christ’s passage from death to life, from the world to the Father, with his triumph over death and sins. In this liturgical context, after having “tasted” the parable of the prodigal sons (yes, “sons” not “son,” because it also and above all concerns the eldest son, the one who is “near” to the Father), today we have another jewel of the Gospel narrative: the episode of the adulteress with Jesus. Here we have a “daughter” who returns to the Father’s presence, albeit in peculiar circumstances. The story is short, but with curious details, full of hidden theological and spiritual meanings. Let us rediscover these details to better understand Jesus and his mission, so that we may be fascinated and attracted even more by the Word of God, merciful and pitiful, slow to anger and great in love and forgiveness.

1. The Scene with the Woman “in the Middle” in the Context of Jesus’ Mission

To understand the message of today’s Gospel episode, we need to clarify its literary context. Although it occurs only in the Gospel of John, our passage with its concise and lively style does not seem to belong to the fourth evangelist, but to the Synoptics, particularly Saint Luke (cf. 7:36ff; 19:47-48; 21:37-38). Nevertheless, the story fits well with what is before and after it in John’s gospel. The overall literary context is the Feast of Tabernacles, which is a grateful reminder of the time when the Israelites walked in the desert, living in tents (tabernacles). They were accompanied then by the presence of God who guided them with the pillar of cloud/fire day and night and granted them grace upon grace, in particular water from the rock and manna from heaven. Jesus was, at that time of the Feast, in Jerusalem celebrating with the people. Immediately before the passage, we find the heated discussion between the Jews and Jesus about His origin and that of the Messiah. On the last day of the Feast, Jesus invites those who are thirsty to come to Him to drink, reiterating a fundamental aspect of His mission, “Let anyone who thirsts come to me and drink.Whoever believes in me” (Jn 7:37). Immediately after our passage, Jesus declares He is the light of the world and confirms the truthfulness of His testimony of Himself and of His divine origin. Such a literary context with a clear messianic and missionary perspective should be kept in mind, because it helps to better understand the meaning of Jesus’ action in our passage.

The description of the initial scene of the story is very detailed and of great importance for the unfolding of the episode, “Early in the morning he [Jesus] arrived again in the temple area, and all the people started coming to him, and he sat down and taught them.” Thus, Jesus is presented as a Teacher/Master in the Temple (as he had been such since he was twelve years old; cf. Lk 2:41ff; 19:47; 20:1) and so he will be called even by his “adversaries” in the story (“Teacher… So what do you say?”). The moment is solemn, almost like that of a nowadays lectio magistralis: “in the temple… sat down… taught them”. It is precisely while carrying out his mission to teach God’s words to the people that “[the scribes and the Pharisees] brought a woman who had been caught in adultery.” The case then is no longer just a case, to use a wordplay. It becomes representative of the whole of Jesus’ teaching, a central illustration of the essence of the message conveyed by God through Jesus, the one God sent to the world.

In such a setting, the position of the woman is also significant: “[they] made her stand in the middle,” (of them). It looks like the indication of the place for the accused in court! The atmosphere then is that of a solemn judicial process or interrogation (cf. Acts 4:7). Perhaps this is an intentional emphasis, because it is repeated at the end of the episode (cf. v.9) where, curiously enough, the woman still stayed “in the middle,” even though those who had brought her and placed her there have already left. The woman therefore was and remained the accused, the guilty one, waiting for judgment.

2. The Scribes and the Pharisees’ Questioning and Jesus’ Mysterious Actions

The scribes and the Pharisees asked Jesus for a judgment on this defendant “in the middle,” not because they did not know what to do. On the contrary, they confirmed before Him their judgment according to the Mosaic Law, “Teacher (…) in the law, Moses commanded us to stone such women. So what do you say?” The antithesis between Moses and Jesus the Master is more than clear. The Law of Moses, that is, the Law of God Himself, transmitted to Moses on Mount Sinai, prescribes stoning without ifs or buts for such cases (cf. Lv 20:10; Dt 22:22-24; Ez 16:38-40). However, they wanted to hear Jesus’ own verdict, “what would be Your word of judgment?”

These scribes and Pharisees knew God’s Law well, and the intention was only to challenge Jesus, since He claims to be from God and to know Him (cf. Jn 7:29; 8:55)! Far be it from us to make any hasty judgment against them. On the contrary! They are not evil or ruthless persons, but simply zealous for God and for His Law (like a certain Jew called Saul from Tarsus). The clash here was not so much between these Jews and Jesus, but between their knowledge of God through the Law and that witnessed by the living Jesus. Attention then for each of us: Learn zeal for God and His Word, like the scribes and the Pharisees, but avoid their mistake of not listening to Jesus, for He is now the only “interpreter” of the invisible God and the full fulfillment of the divine Law (cf. Jn 1:18; Mt 5:17-18). So, you too seek to know Jesus more and more through living in the spirit of constant prayer (i.e., constant listening) in order to have true knowledge of God and His law (acquired also through study). In this regard, perhaps we need to meditate on the case of the Pharisee Saul who became Paul and re-read his moving confession of Phil 3:8-14 in the second reading of this Sunday, “I consider everything as a loss because of the supreme good of knowing Christ Jesus my Lord. For his sake I have accepted the loss of all things and I consider them so much rubbish, that I may gain Christ and be found in him, not having any righteousness of my own based on the law but that which comes through faith in Christ, the righteousness from God, depending on faith to know him and the power of his resurrection and the sharing of his sufferings by being conformed to his death, if somehow I may attain the resurrection from the dead.”

Returning to the Gospel story, we note a curious action of Jesus in response to the scribes and the Pharisees: he said nothing, just “bent down and began to write on the ground with his finger.” It is the only New Testament passage that mentions Jesus’ act of writing. However, one should avoid the speculation many have made and continue to make, “What did he write?” Maybe the sins of each of the present Pharisees and scribes? (This is hypothesis from the early centuries, evidenced in some ancient manuscripts.) Their names? (as noted in Jer 17:13: “all who forsake you [the Lord] will be put to shame. Those who turn away from you will be written in the dust because they have forsaken the LORD, the spring of living water.” [New International Version])

In fact, it seems that the Gospel text wants to emphasize the act and not what he wrote. Therefore, only the action of Jesus, described twice (vv.6.8) is important and must be contemplated together with his word, in order to understand the meaning of the story and the reaction of the Pharisees and scribes. As noted by some careful exegetes, Jesus’ action of “writing with his finger” seems to reflect that of God himself on Mount Sinai who wrote with his finger the Law for Israel. From this perspective, Jesus’ bending down echoes that of God, who bent down to the earth from heaven. Moreover, the repetition of the writing act seems to refer to God’s rewriting of the tables of commandments, because they were shattered by Moses in the face of the people’s sin of idolatry, in the episode of the golden calf! All these details lead to grasp the main message of Jesus’ actions: He reminds all that the true Lawgiver is God Himself who alone has the competence to judge men and women. Indeed, Jesus acted now as and in the place of God the Judge. He, therefore, launched a challenge to those who had tested him, “Let the one among you who is without sin be the first to throw a stone at her” (because actually all have sinned, as seen in the mentioned story of the golden calf). Everyone who feels like God, the only just judge because he is without sin, let him do justice! In the words of Jesus, we hear all the force of what Saint James would later say to some Christians, admonishing them because they too loved to judge others (as if it were their favorite sport!): “There is one lawgiver and judge who is able to save or to destroy. Who then are you to judge your neighbor?” (Jas 4:12). (Obviously, this warning also applies to our examination of conscience in this last phase of Lent for possible repentance!).

The scribes and the Pharisees, “in response, went away one by one”, because perhaps they had understood Jesus’ message well, expressed in unusual but eloquent words and gestures, “beginning with the elders” (not so much because they were more sinful, but perhaps because they were the first to understand, the wisest and most expert of Scripture).

3. The Misery Adulteress and Living Mercy

In this way, we arrive at the end with a very evocative image. “So he was left alone with the woman before him”, literally “in the middle.” As mentioned at the beginning, the woman still remains “in the middle,” an accused person in court awaiting judgment; but now there is only Jesus, the only divine judge. Thus, from a spiritual point of view, St. Anthony of Padua, Doctor of the Church, “sees” the woman standing “in the middle” between the mercy [of Jesus] and the justice [of the Pharisees]. The Gospel scene is so beautiful that it inspired St. Augustine to leave a wonderful laconic commentary, which has become famous: Relicti sunt duo, misera et misericordia! “The two of them alone remained: mercy with misery” (also mentioned by Pope Francis in his Apostolic Letter Misericordia et misera).

Thus, in an encounter perhaps never thought of and somehow “forced” by divine Providence, the adulterous woman remained alone with Jesus the Master. She waited for a word of judgment from the one whom she now calls Kyrios “Lord” (rather than just a polite “Sir” in some modern English translations), with all respect and perhaps already with some expression of faith and hope in Him. And Jesus’ answer was probably unexpected for her, “Neither do I condemn you. Go, and from now on do not sin any more.”

The judgment is pronounced within a cordial dialogue with the woman, in the manner of the teachers of that time (“Where are they? […] No one!). Jesus’ judgment confirms the announcement of his mission in Jn 3:16-17: the Son is sent by God not to condemn but to save. The “I do not condemn” goes, however, with the command to sin no more. The judge reveals Himself to be merciful in the face of human misery, but at the same time uncompromising against sin, for He knows that sin makes those who do it pay the consequences. Jesus’ recommendation should therefore be understood as that to the lame man after his healing, “Do not sin any more, so that nothing worse may happen to you” (Jn 5:14).

The Gospel of John does not tell us more about this nameless woman. She appears and disappears from the scene in the same way, suddenly and mysteriously. We know nothing about her future after she experienced the great “justice” of God in Jesus, a divine justice that reveals itself in reality as “love, mercy and fidelity” for the salvation of humanity. On the other hand, other gospels inform that among those who followed Jesus in his mission of evangelization there were also “some women who had been cured of evil spirits and infirmities” (Lk 8:2). It would not be totally unreasonable to imagine the today’s adulteress among those faithful followers of the Messiah. (Some thought it was Mary of Magdala, who would later be called to become the first “apostle” [missionary] of the risen Christ). In any case, after “having been granted mercy” by Jesus, (or “[being] mercied”, to imitate a fine Italian neologism “misericordiata” of Pope Francis (cf. Regina Caeli, Church of Santo Spirito in Sassia, Sunday, 11 April 2021), she has certainly become a living witness and announcer of divine mercy among her people, just like the Samaritan woman after her “accidental” encounter with Jesus near the Jacob’s well (cf. Jn 4:5-30). It will also be an invitation for all of us as well as for every man and woman to take the same path, no matter how complicated the situation in which we find ourselves: to go to Jesus to experience divine mercy and then to witness to the world the Lord’s grace.