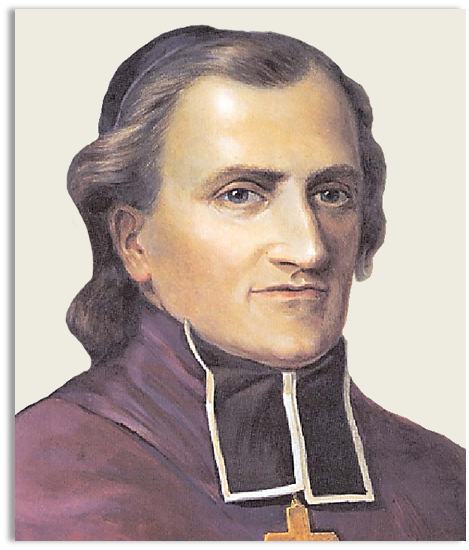

Charles de Forbin-Janson was born in Paris, in 1785, into a noble and Catholic family. It grows in a family environment shaped by faith in God and fidelity to the Pope and the Church. From an early age he was attentive to the needs of his peers. At 18 he entered the military academy and then continued his studies in Paris. With the arrival of Napoleon, the ecclesial situation in France changes and becomes critical.

So, after giving up the role of member of the Council of State nominated directly by Napoleon, Charles decides to become a priest to put himself at the service of God in the Church, in particular to defend the Pope, to restore faith in his now anticlerical France and to evangelize the world.

During the seminary period, Charles attends the chapel of foreign missions in Paris, begins to listen to the stories of the missionaries about their work in China and the thousands of children that priests and nuns welcome, care for, educate, baptize and teach them to live according to Christian values.

In his spare time he dedicates himself to catechism for the children of his parish and teaches them to pray. He considers himself lucky to have received a good Catholic education from his parents. Think continually of those poor children who cannot grow in the beauty of faith, of the many children in China who have no one to teach them who God is.

It is 1809 and Pope Pius VII is arrested by Napoleon. Two years later Charles is ordained a priest. His missionary spirit grows and strengthens. At 38 he was ordained bishop of Nancy and immediately began organizing retreats and missions in all the parishes of his diocese. Even as a bishop he lives in a very simple way, despite having had an experience of a noble and rich life, and he says: "My greatest joy is to make others happy". He continually distributes his wealth and keeps very little in his wardrobe.

During his absence from the diocese for pastoral duties, the anti-clerics sack the episcopal seminary and prevent him from returning to Nancy. The saddest period of his life begins: exile. But keep thinking about the missionaries and children of China. After three years of mission in North America, she returns to France and, in Lyon, meets Pauline Jaricot, the founder of the Work of the Propagation of the Faith, and talks with her about her wishes and ideas. He himself had been one of the first bishops in France to establish the work he founded in his diocese and continually encouraged priests and faithful to support missions through that work. Even in exile he had continued to do the same.

The bishop met Jaricot a second time, the decisive one for the start of a new work. What she had organized for adults in France, he would have organized for children from all over Europe. Charles was overjoyed: the children would help their brothers and sisters and not only those of China, but of all the missions in the world. This project would have had a double benefit: to give material and spiritual help to the children in the missions and to make those in Europe discover the virtue of charity towards others: "There is more joy in giving than in receiving" (Acts of the apostles, 20, 35). In this way, like the baby Jesus, they would grow in age, wisdom and grace before God. The future is built from the present.

Following Pauline's suggestion, Monsignor Charles thinks of something simple and small that would have made the children holy: a short daily prayer and a small monthly sacrifice. And precisely through these two missionary tools the children of the world would be united.

It is May 19, 1843: the Work of Holy Childhood is born and in its name there is the will of Charles de Forbin-Janson to entrust it to the protection of the baby Jesus. The following month, the event is solemnly announced in the parish of origin of the prelate and a circular is sent to all the bishops of France. The majority are in favor of this new initiative, but some are concerned about a possible interference with the work started years earlier by Jaricot. These perplexities disappear when it is known that it was Pauline herself, together with Charles, who wanted the creation of a separate work for the children and that she herself had been the first to make an economic contribution for it.

The project takes place: the work awakens European children to the needs of other children in a new dimension of missionary awareness: transmitting a gaze and a missionary heart from childhood. On December 8, 1843, having seen the spread of the work also in Belgium, Charles wrote a letter to eleven missionary bishops assuring them of support, in particular for the baptism of children and Christian education. Emphasize that help is from children for children, for their spiritual and material well-being.

In the spring of 1844, consumed by evangelizing effort and missionary zeal, Monsignor Charles agreed to withdraw, however continuing his correspondence with the French priests and the missions. In May of the same year, Pope Gregory XVI approved the work of Holy Childhood.

On 11 July 1844 Charles dies. Peacefully and with the latest thought dedicated to Holy childhood.